UPDATED because I forgot about Rick Steves!

Time, time, time. Time is endless and instant and immeasurable now. I have many thoughts on what that means for me personally and professionally, but for now, I want to be light.

Some ways I’ve been spending my time…

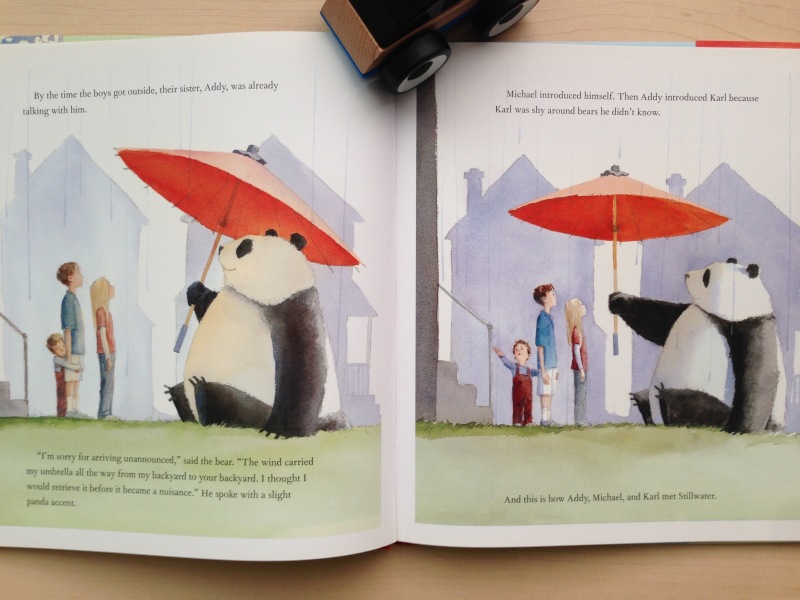

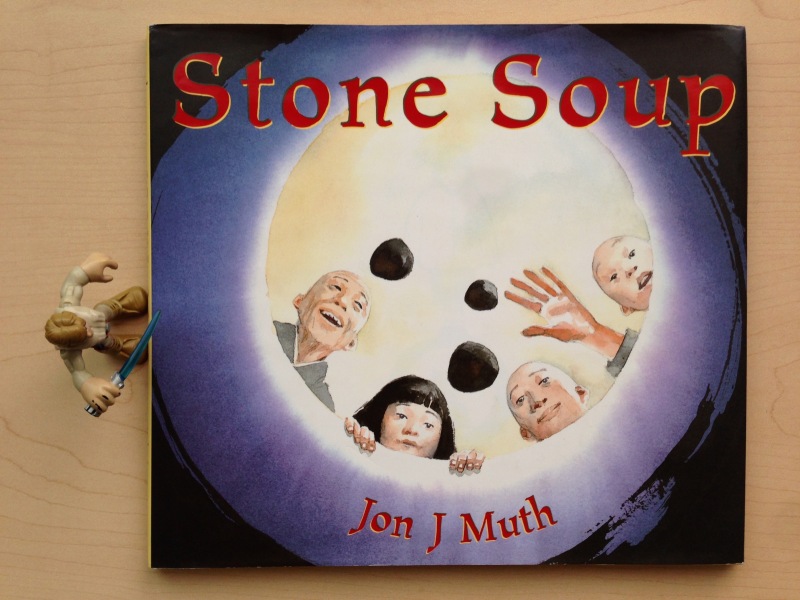

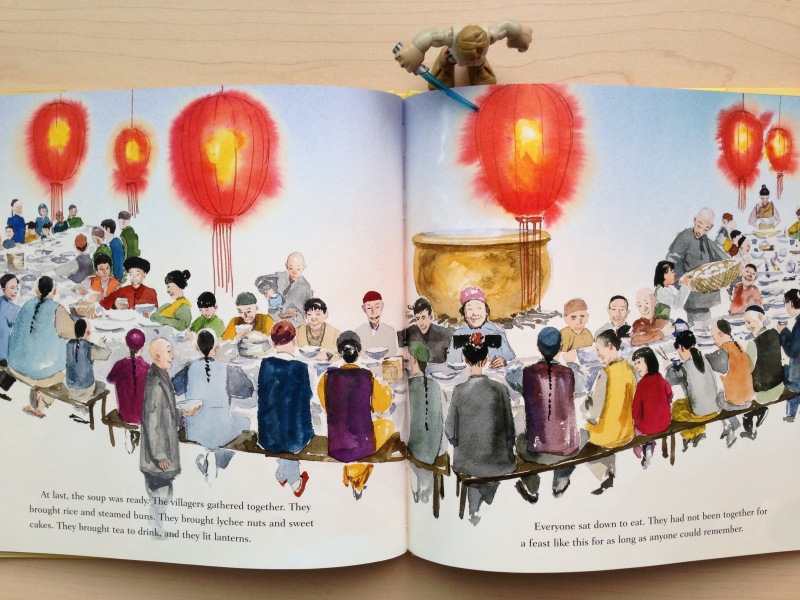

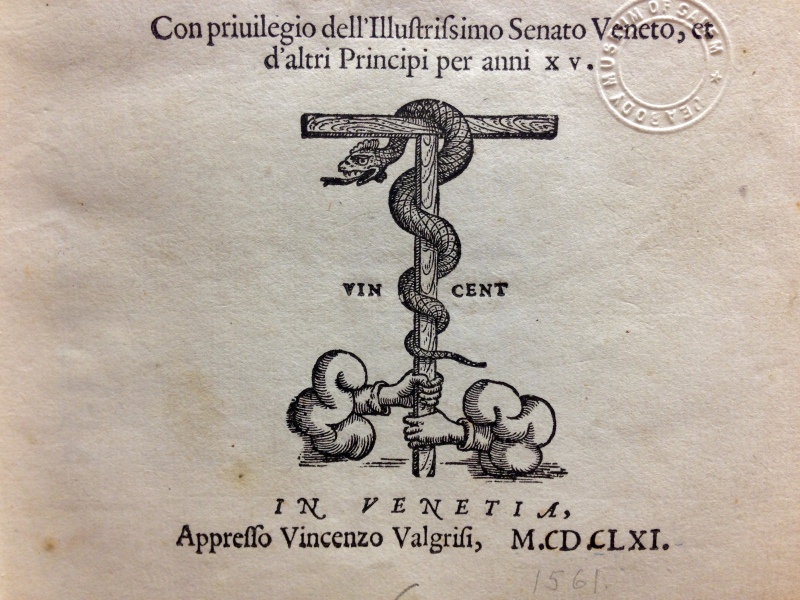

With books

I told myself that, without my Powell’s discount, book buying would just to wait until I returned as an occasional (or started otherwise earning regular income). COVID obviously put paid to that, plus my natural inclination to collect is really, really hard to resist…

I’ve bought some books for work. I have to call out one in particular. Placing Papers: The American Literary Archives Market, by Amy Hildreth Chen, is extremely relevant to my work in appraisal, and it is revelatory for the trade in general. In some ways, it is ominous, but a more optimistic word would be “cautionary.” In reviewing the market in authors’ papers, from creator to dealer to repository, Dr. Chen makes clear that the Matthew effect (rich/famous creators sell papers to rich/famous institutions) is ongoing, and now it is likely to get worse thanks to COVID financial upheaval. This has major implications for the trade and libraries (and researchers), even as they look to diversify and be more inclusive, and for my work in appraisal, a field caught somewhere in between the two.

Other books of note that I adore:

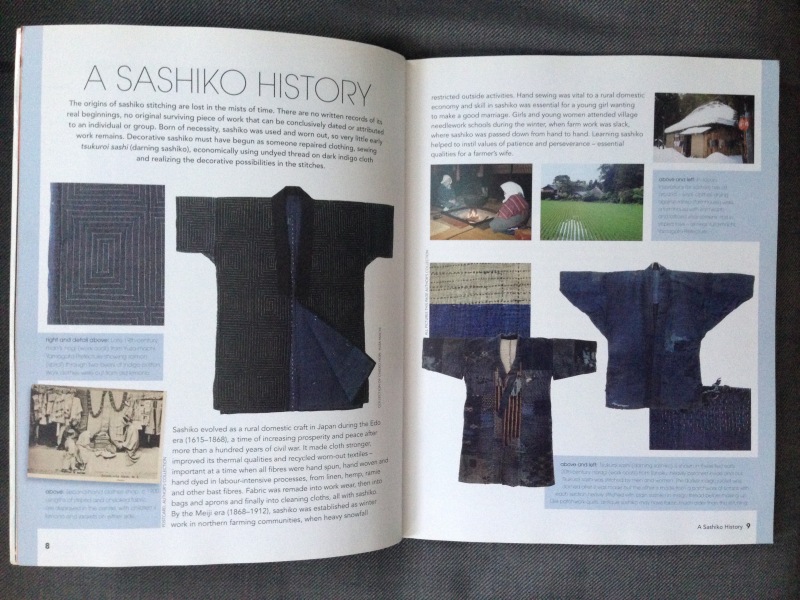

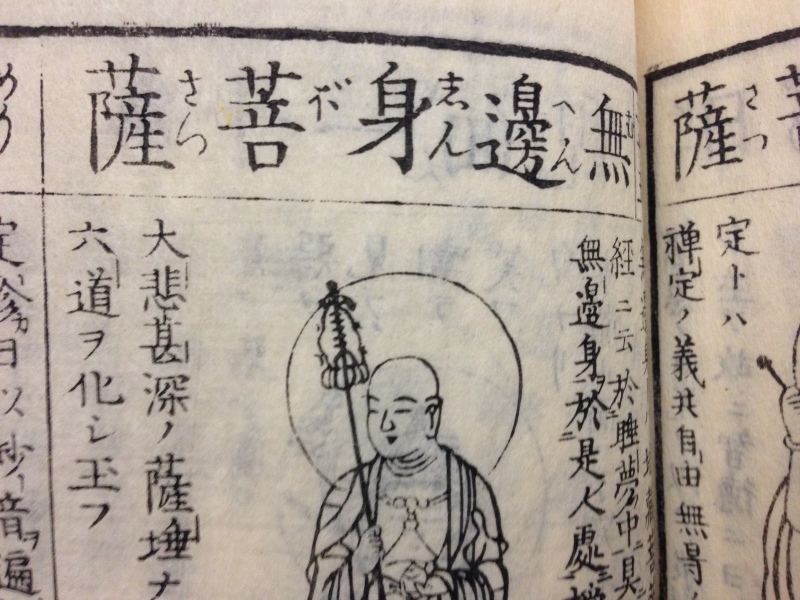

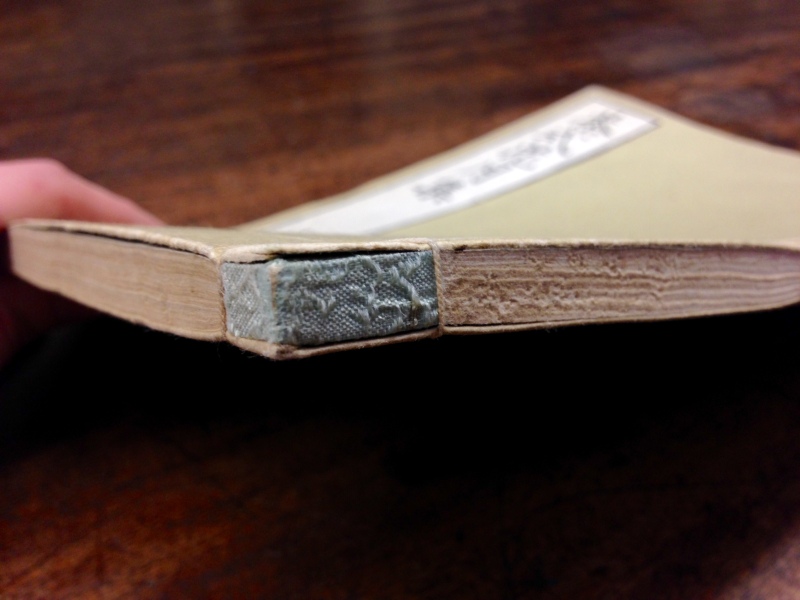

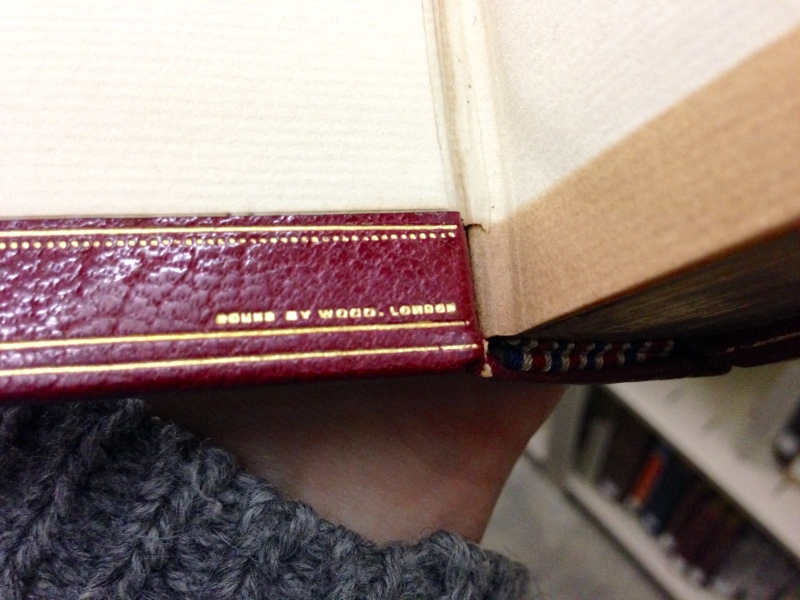

A Song of Praise for Shifu, by Susan J. Byrd. A stunning book published with typically thoughtful care by Legacy Press, mine is one of the first editions with the original samples of shifu (a Japanese paper-based textile). It was also from the collection of esteemed bookbinders Monique Lallier and Don Etherington, though there is sadly no evidence to show that.

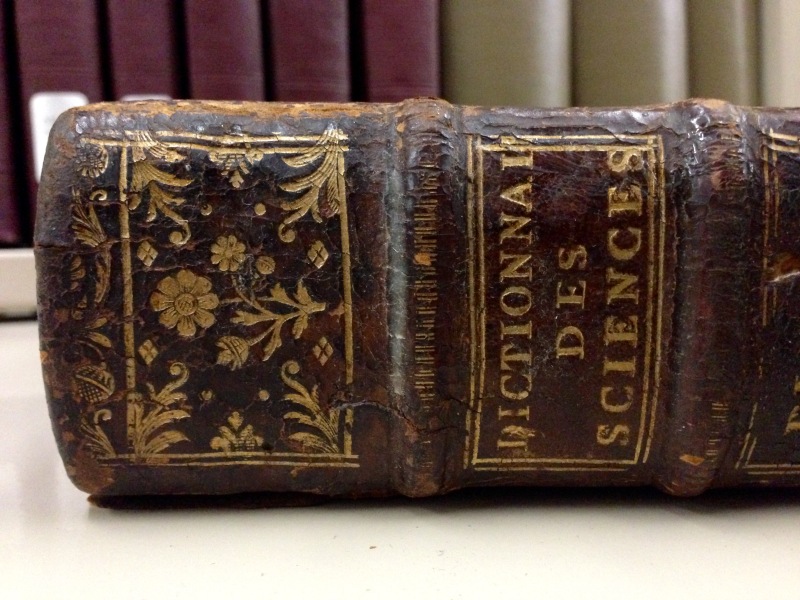

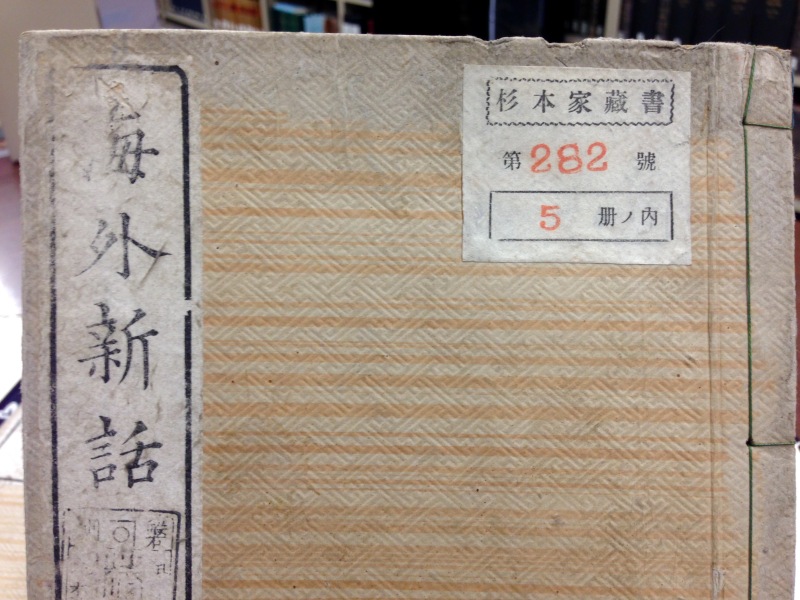

Book Collecting in Chinese Culture, by Sang Liangzhi. I’ve been putting this book off for a couple of years now, because I could never find it for an affordable price. Finally, my research into Chinese book collectors’ seals pushed me over. It was worth it! The translation is charmingly quirky, and I’m going to have to work to make its citations clearer to me, but it has been so informative already.

Inks & Paints of the Middle East, by Joumana Medlej. Meticulously researched and clearly illustrated, this book is so inspiring. The author also makes pigments and pens, which you can buy in her shop. Follow her on Twitter to watch her research play out, see her art-in-progress, and find ways to help artists and creators in Lebanon.

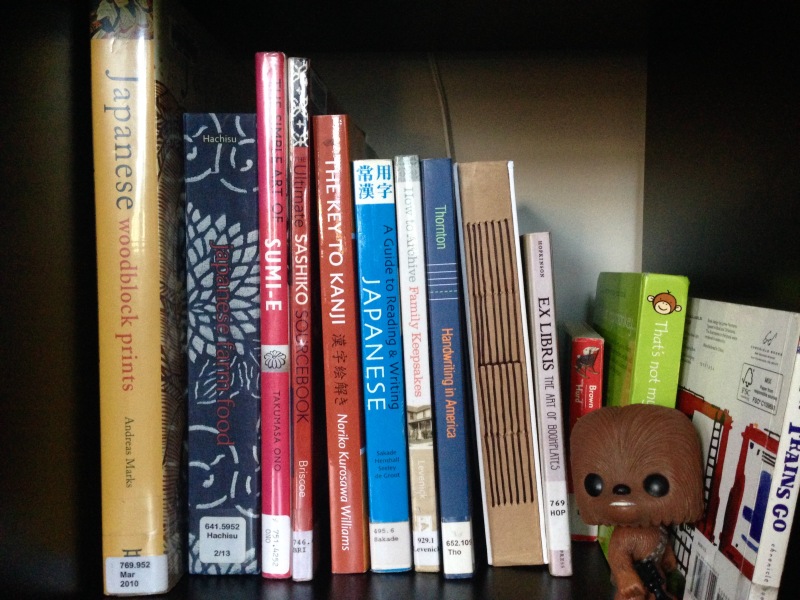

So what do I do with all these books? Currently, embarrassingly, I pile them everywhere. There are stacks surrounding my desk, stacks under the bed, stacks supporting the kiddo’s Lego structures. Personal books are interspersed with library books, kid books, and notebooks.

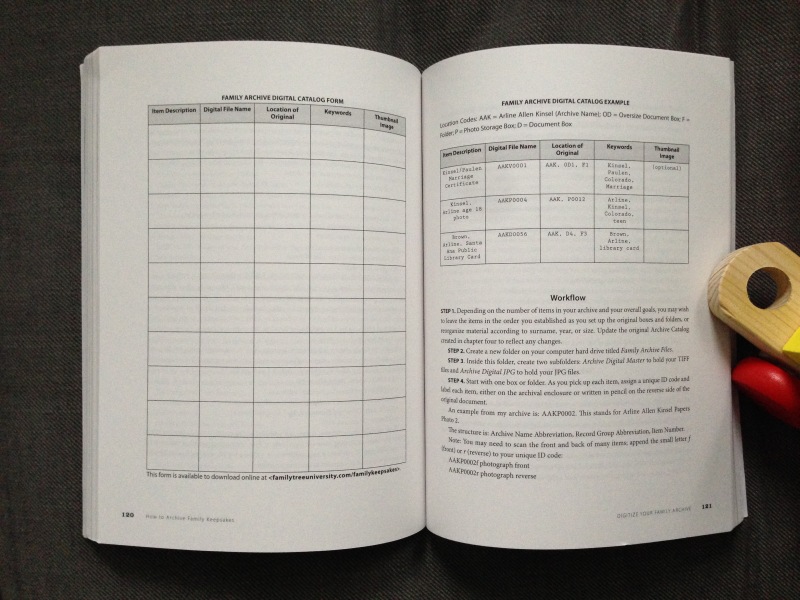

But I still have a tenuous hold on the situation. I love to catalogue books. I’ve tried a number of systems, from Book Collector to Delicious Monster to spreadsheets to handwritten lists. Delicious Monster in particular worked for a few years, but I eventually wanted something more robust and library-friendly, so I migrated to LibraryThing. It’s denser and perhaps less glossy than some of the other options on the market now, but I find it invaluable. I love connecting to libraries with books in common, the intensely bookish lists and data, and the fact that I can immediately see that 537 of my catalogued books came from Powell’s. As a once and future librarian, I adore that I can have a public library catalogue of my very own.

I even read books sometimes…

But my world is mediated more and more through digital means.

With screens

I haven’t done as much binge-watching as I probably could have, being stuck at home for so long. On the flip side, I haven’t really explored much new screen entertainment.

I’ve rewatched the entire run of Avatar: The Last Airbender (thank you, Netflix!) more than once. I’ve been crushed by the news that its creators have left the live-action project (damn you, Netflix!).

I’ve started and not finished The Mandalorian, Good Omens, and Star Trek: Picard. I really enjoyed each, and I swear I’ll get back them…

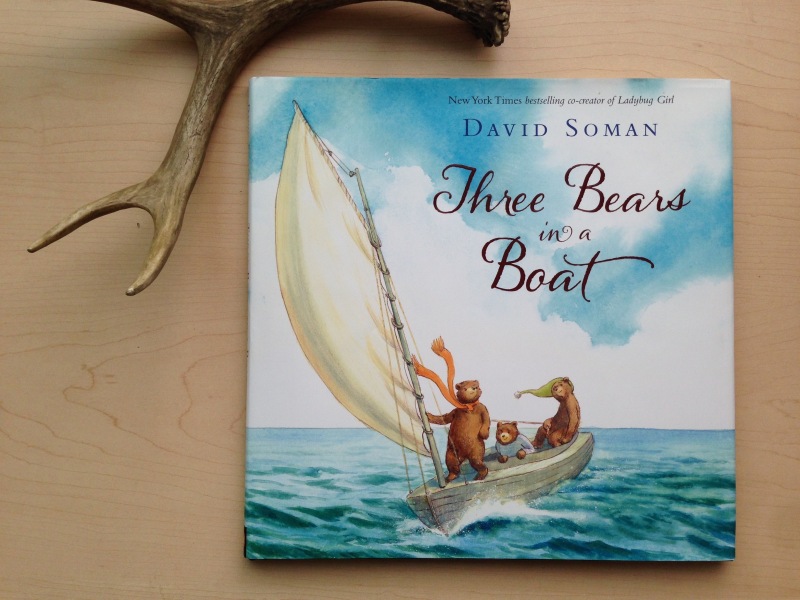

M turned me onto Sampson Boat Co.’s YouTube channel. The incredibly charming Leo Sampson Goolden is restoring a 1910 sailing yacht up on the Olympic Peninsula. I have no experience with boatbuilding, but his videos are informative, gentle, and inspiring beyond the craft. He is matter-of-factly knowledgeable, digs in and works hard, and is generous with his enthusiasm and attention. If you like seeing craft undertaken with heart, binge this. You won’t regret it, even as the COVID crisis creeps in to the recent posts.

I recall watching a lot of “The West Wing” during the W years. But either I’ve changed or the Wing hits too close to home (both true, really), and it just doesn’t work for coping right now. Star Trek can seem more remote, therefore more appealing. But even my standby Voyager and Next Generation are sometimes too blandly utopian (or dystopian, depending on your take). I started watching Deep Space Nine from the top for the first time, and it has hit the spot so well. It has the post-Roddenberry longer arcs and inter-character conflict. The storylines have parallels to our current world, and it actually includes plenty of non-Earth-historical cultural touches. It’s colorful and complex and troubling, and it walks the fine line between inspiring and grounding that I need right now.

To help compensate for cabin fever and wanderlust, our little family has been watching a LOT of “Rick Steves’ Europe.” He likes churches more than I do, but his down-to-earth approach is appealing and often leads to long discussions with M. I even checked out Steves’ Travel as a Political Act and will be reading that soon. Plus, it’s helped us add to our dream travel itinerary. Turns out that Eastern Europe and/or the Balkans flew too far under our radar before. We are really intrigued to visit someday.

When I really need to get away, though, I play games. M has been playing Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey, which is stunning. I want to get the Discovery Tour version, though. All the killing actually really gets in the way of enjoying the scenery.

My primary game of choice is Elder Scrolls Online. I’ve been playing for years now, and it is (usually) a solace. If you don’t know the Elder Scrolls series, it’s a deep open-world RPG franchise. The lore is intricate and fascinating, and the cultural development is mostly fantastic. Part of the world story includes racism, slavery, and a strong sense that there is no clear good or evil, and some of it is off-putting. (These days, I look at everything with a critical eye to diversity and appropriation. It dampens enjoyment sometimes, but it’s essential practice for progress.) ESO is also, unlike Skyrim and previous Elder Scrolls games, an MMO. That means the chat sometimes goes down unpleasant roads, but the community is generally excellent, and bigoted posts usually get reported and shouted down very, very quickly.

One cool diversion that ESO led me to recently was the inaugural ArchaeoGaming Con. There is a robust community of archaeologists who work in and around games. Since ESO recently implemented an Antiquities system that involves excavating artifacts around the game world, it was really fun to watch this conference unfold. ESO has a surprising amount of storylines and conversations that touch on cultural heritage, so it often ties into the work I do in the real world.

With Zoom

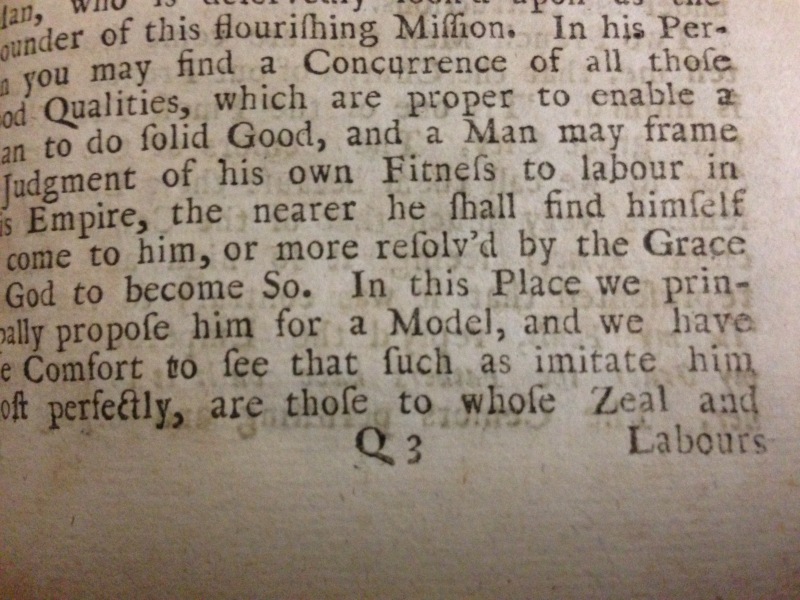

… and other online webinars. Since I’m unable to do most of the work I was planning before COVID hit, I’ve spent a lot of time attending web presentations and classes. I’ve attended most of the presentations by the Rare Book School and the Bibliographical Society of America, as well as a scattering of others from around the general cultural heritage sphere.

I particularly want to call out a few:

A Hornbook for Digital Book History, by Whitney Trettien

This talk was conceptual and enthralling. I was so inspired by her ideas and her suggested model for considering bookish objects. I’m still thinking about it.

Records of Deception: Forgeries and the Integrity of the Historical Record

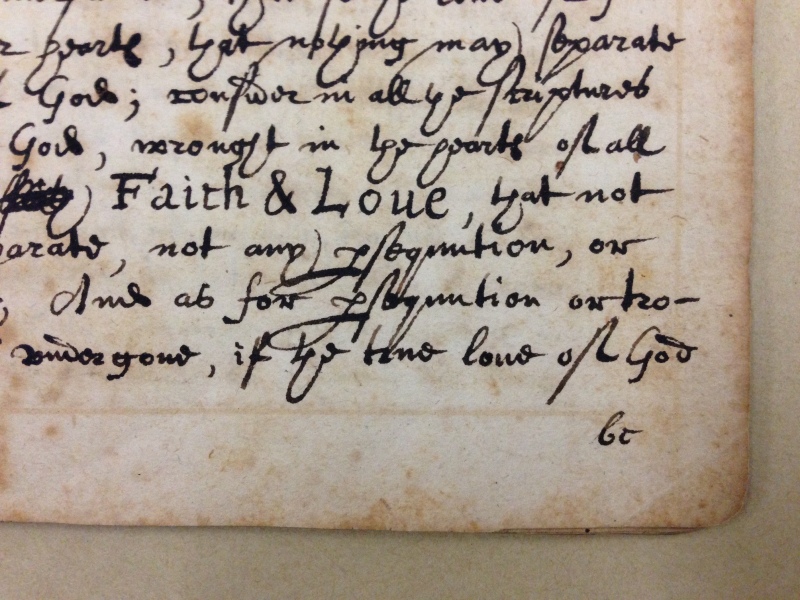

I’m fascinated by forgery and other aspects of cultural heritage crime, and this wide-ranging discussion was so cool. It was an historical and bookish slant on the current fake news and disinformation deluge.

(H)EX-LIBRIS: Tracing Occult Identities, by Kim Schwenk

I knew I would enjoy this, but it was so much more expansive than I expected. Cataloguing and description are the way to intellectual access of materials in libraries and archives (and bookstores, for that matter). The serendipity of the stacks is fun but unreliable as a direct route to knowledge. One thing that can be hard to grasp is that a book can be sitting on the shelf, but if you can’t find it through the catalogue, it might as well be invisible. Occult, by its very definition, is secret. So how do we bring these works and creators to a larger audience?

Outside of RBS and BSA, Icon Book & Paper Group ran a Conservation at Home series, and this session in particular was amazing:

Divine Conservation: What can 500 tarot card decks tell us about conservation?

This talk was presented by MIT Libraries staff and centered on their collection of contemporary indie tarot decks. It touched on acquisitions, multi-format (including jelly beans!) preservation, and access. I have never had to consider the idea of cleansing the energy from archival collections before, but now I really want the tarot deck they’re producing.

Finally, one series I have found deeply informative and inspiring is the Culture in Crisis series on Post-COVID cultural heritage strategies, put on by the British Council, DCMS, and the V&A. Unfortunately, I don’t think they plan to make the videos available publicly, which is a shame. The series has offered a broader (if primarily archaeology-oriented) perspective on cultural heritage access and protection during and beyond COVID. Cultural heritage stewards and scholars from the UK, US, and Middle East spoke about looting, destruction, education, conflict, colonialism, and more, and it was heartbreaking and heartening at the same time. I sincerely hope we are working toward change.

With writing

…because, holy shit, is it easy to get stuck in my own head right now.

I like to be alone, but I’ve discovered that there are limits (also, I am now NEVER ALONE). What I hoped would be time to relax and make plans and take remote action and think and muse occasionally turns into time to get really, really overwhelmed. I’ve always used my diary, my notebooks, and other writing as a way to work this out, but now it’s more important than ever.

My notebook of choice is a Leuchtturm1917 A5 hardcover, grey with dotted pages for daily notes, black ruled for my diary/journal. My diary writing is typically slow-going, because I have a tendency to put it off until the “perfect moment” (which is rare). My daily notebook has become an even more essential repository for scheduling, notes, thoughts, and tracking, and I just had to order two more, because I have filled 2.5 of them just since lockdown started.

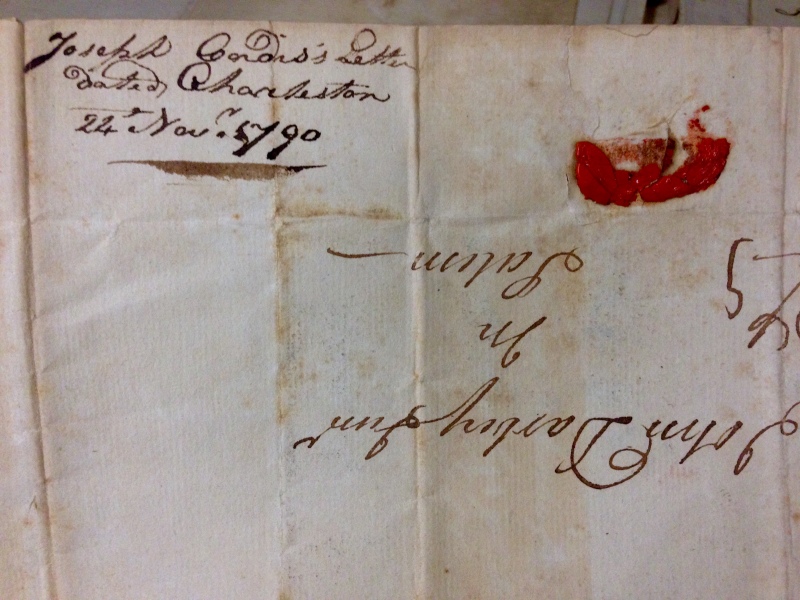

I’ve also picked up some penpals! I’m not a very good snail mail correspondent yet, but I’m working on it. How can I not, when I’m sent such gorgeous mail? I signed the kid up for some informal correspondence with friends’ kids, but he doesn’t know it yet… We’ll see if it works.

And hey, I resurrected my blog a bit. I look forward to a burst of posts, hopefully not followed by my usual distracted apathy.

With looking forward

Somehow, I still consider myself an optimist, or at least a positive realist. Despite the truly incredible amount of crap going on in the world right now, I still manage excitement for things.

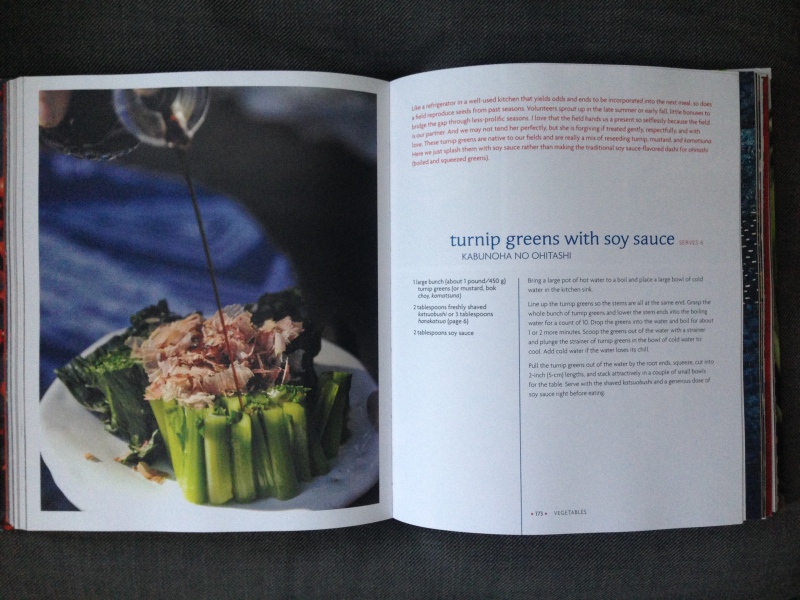

Like foodie things! I tried Dalgona coffee, which went… okay. Tasty if not pretty. I’m trying to shift precedence to my tea fascination, though. I’m sure I’ll have more to say on that.

And work! All these webinars and classes and books have given me a lot of ideas for professional direction. But I’m going to save that discussion.

So instead, books! A short list of the books I’m eagerly anticipating:

- The Galaxy, and the Ground Within, by Becky Chambers

- The Oxford Illustrated History of the Book, edited by James Raven

- The Rise of the Arabic Book, by Beatrice Gruendler

- Baggage: Confessions of a Globe-Trotting Hypochondriac, by Jeremy Hance

- Piranesi, by Susanna Clarke

- Hernando Colón’s New World of Books: Toward a Cartography of Knowledge, by José María Pérez Fernández and Edward Wilson-Lee

- His Dark Materials: Serpentine, by Philip Pullman

- Information: A Historical Companion, edited by Ann Blair, Paul Duguid, Anja-Silvia Goeing, and Anthony Grafton

- Xu Bing: Book from the Sky to Book from the Ground, by Xu Bing

- Agatha Christie’s Poirot: The Greatest Detective in the World, by Mark Aldridge

- Dark Archives: A Librarian’s Investigation into the Science and History of Books Bound in Human Skin, by Megan Rosenbloom

- Against Amazon and Other Essays, by Jorge Carrión

- Burning the Books: A History of the Deliberate Destruction of Knowledge, by Richard Ovenden

- Signature (Object Lessons), by Hunter Dukes

- A Psalm for the Wild-Built, by Becky Chambers (yes, she gets two, she is worth it)

With learning when to break

Despite the upheaval of quitting my full-time job, onset of COVID life, and the ongoing slide into authoritarianism, I didn’t cry until… mid-April? It hit me suddenly and confusingly, and then I wept and realized that was the key. Since then, I’ve cried occasionally, and it has always made me feel better (though not always instantly).

I’ve also started taking regular walks, instead of relying on in-home exercise for everything. Even neighborhood nature has helped immensely.

I am extremely lucky (even if I have to remind myself sometimes) to have so much time with my young son. How many parents have the chance to spend long hours with their school-age kids? How many parents get to see so much of their growth? Sometimes I just watch him play or read, and it is mind-blowing.

Finally, I stop. I feel such a desperate need to let words out lately, but even that faucet needs to be turned off sometimes. Like now.

Be well, everyone.